History

The Museum of Bad Art began in the early 1990s after a discarded painting inspired its founders to showcase art that is “so bad it should not be ignored.”

MOBA celebrates “art too bad to be ignored.” The focus is not on mockery, but on honoring earnest artistic effort. The museum encourages viewers to consider creativity, intention, and the subjective nature of artistic judgment, reminding us that the courage to create is valuable, even when the outcome is delightfully imperfect.

The Museum of Bad Art began in the early 1990s after a discarded painting inspired its founders to showcase art that is “so bad it should not be ignored.”

MoBA Zoo

Poor Traits

Location: L1250 Massachusetts Ave Boston, MA 02125, USA

Contact: +1 (781) 444-6757 / MOBA@MuseumOfBadArt.org

The Museum of Bad Art was founded by antique dealer Scott Wilson, who discovered what has become the museum's signature piece—Lucy in the Field with Flowers—protruding from between two trash cans on a Roslindale-area curb in Boston, among some garbage waiting to be collected. Wilson was initially interested only in the frame, but when he showed the picture to his friend Jerry Reilly, the latter wanted both the frame and the painting. He exhibited Lucy in his home, and encouraged friends to look for other bad art and notify Wilson of what they found. When Wilson acquired another "equally lovely" piece and shared it with Reilly, they decided to start a collection. Reilly and his wife, Marie Jackson, held a party in their basement to exhibit the collection to date, and hosted a reception they facetiously titled "The Opening of the Museum of Bad Art".

Regular showings of the pieces collected by Wilson, Reilly, and Jackson (and those donated by others), became too much for Reilly and Jackson's small home in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, as hundreds of people attended the receptions. The founders' initial attempt at dealing with their constrained exhibition space was to create the Virtual Museum Of Bad Art, a CD-ROM with a cast of 95 people that presented the MOBA art collection in a fictional imaginary museum. This fictional MOBA allowed the visitors not only to view the paintings but to go behind the scenes in the fictional museum.

The MOBA was officially founded in 1993, and its first exhibition was presented in March 1994.

Word of the museum's collection continued to spread until, according to "Permanent Interim Acting Director" Louise Reilly Sacco, "it got completely out of hand" when a group of senior citizens on a tour bus stopped to see it. In 1995, the display space was moved to the basement of the Dedham Community Theatre, a building with an aesthetic described in 2004 as "ramshackle". The museum in Dedham had no fixed operating hours, instead being open while the theater upstairs was open. As The Boston Globe notes, the art collection was appropriately placed "just outside the men's room", where sounds and smells carry to the collection and the constant flushing of the toilet "supposedly helps maintain a uniform humidity", according to the South China Morning Post.

In MOBA's early days, the museum hosted traveling shows; on one occasion the works were hung from trees in the woods on Cape Cod for the "Art Goes Out the Window—The Gallery in the Woods". Bad music was played during the public viewings to complete the ambiance. In an exhibition titled "Awash in Bad Art", 18 pieces of art were covered in shrink wrap for "the world's first drive-thru museum and car wash". Marie Jackson, formerly the Director of Aesthetic Interpretation noted, "We didn't put any watercolors in there." A 2001 exhibition, "Buck Naked—Nothing But Nudes" featured all of the MOBA nudes hung in a local spa.

MOBA features its works in rotating collections. In 2003, "Freaks of Nature" focused on landscape artwork "gone awry". A 2006 exhibit titled "Hackneyed Portraits" was designed to "pick up some of the slack" when the David Hockney show at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts closed. MOBA unveiled its show "Nature Abhors a Vacuum and All Other Housework" in 2006; this format continues on the museum's website.

A second gallery opened in 2008 at the Somerville Theatre in Davis Square, Somerville, Massachusetts, where the collection was placed near both the women's and men's restrooms. Although the original gallery was free and open to the public, the second is free with admission to the theater or with a pass requested from the museum. Exhibitions titled "Bright Colors / Dark Emotions" and "Know What You Like / Paint How You Feel" have been held in the academic gallery at Montserrat College of Art in Beverly, Massachusetts. One of MOBA's goals is "to take bad art on the road", according to Sacco. Pieces from MOBA's collection have been on display in museums in New York City, Ottawa, Taipei, and Virginia.

In February 2009, MOBA announced a fundraiser to assist the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University, which was seriously considering whether to sell masterpieces because of the 2008 financial crisis, made worse for the university by some of its donors losing money in the Madoff investment scandal. Current MOBA curator Michael Frank placed Studies in Digestion—a four-panel piece showing four renditions of the human digestive tract in various media by artist Deborah Grumet—on eBay for a buy-it-now price of $10,000; the first bid was $24.99. It eventually sold for $152.53 and the meager proceeds went to the Rose Art Museum, while both museums gained publicity.

In 2010, the museum opened a third location in the offices of the Brookline Interactive Group.

In December 2012, the branch at the Dedham Community Theater closed to convert the space into a screening room. Another branch later opened at the New England Wildlife Center in South Weymouth. The Somerville location was closed in 2019 when theater owners sought to renovate the basement space it occupied. All locations closed after the breakout of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The museum reopened at the Dorchester Brewing Company's tap room in Boston in September 2022.

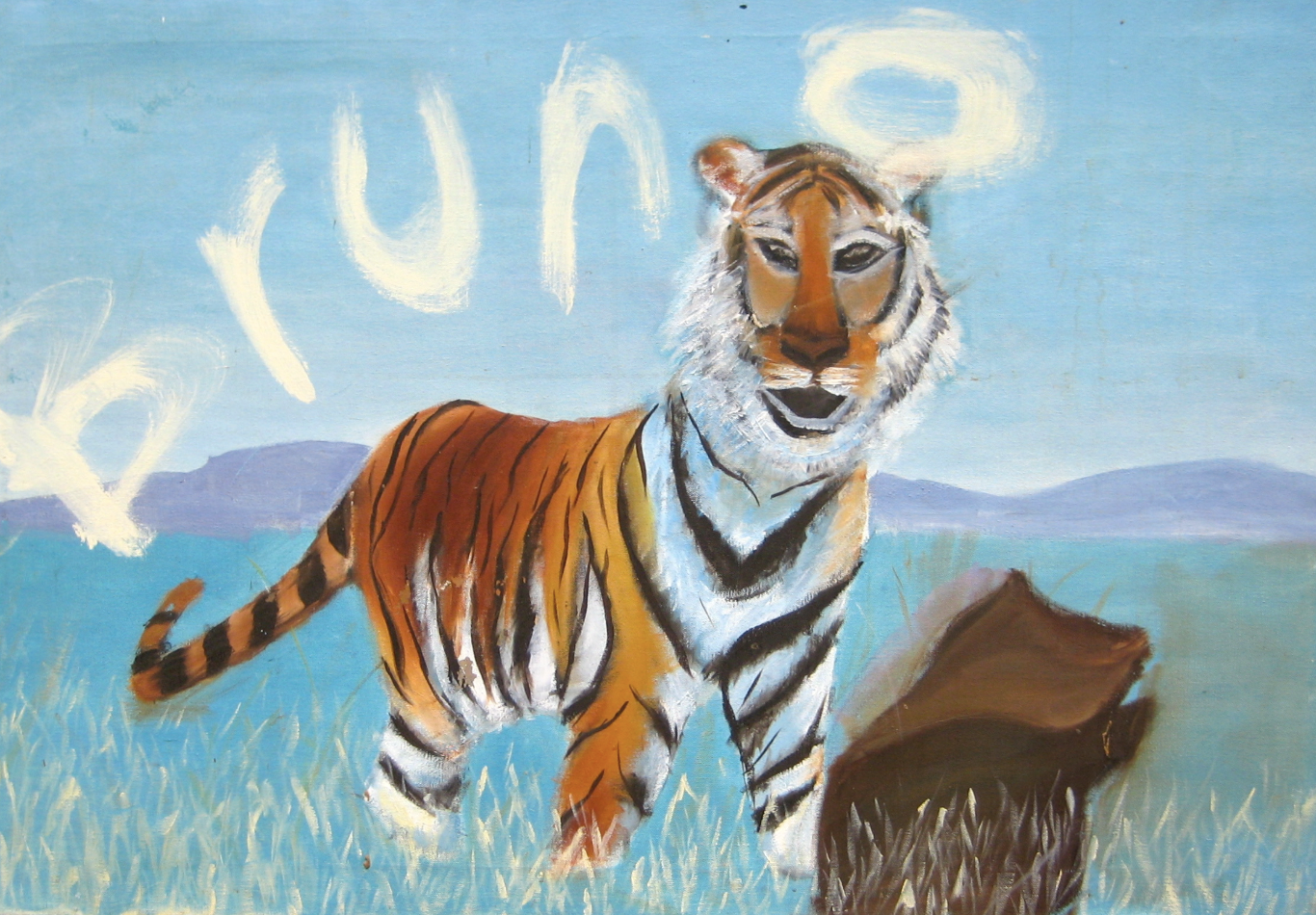

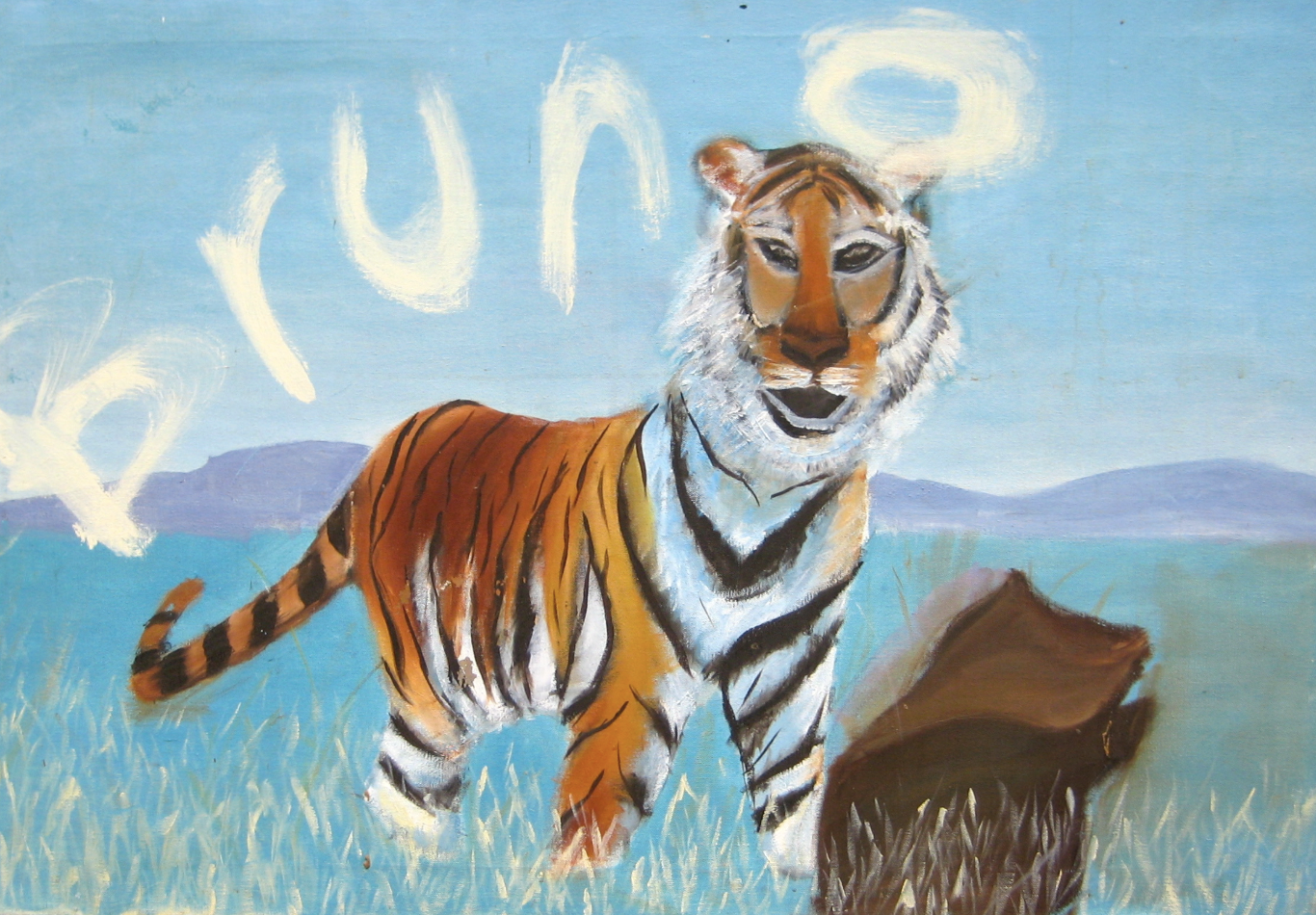

Bruno Tiger

Anonymous • June 2010

Pink Woman Ascending

Anonymous • October 2010

Point of Impact

Anna K. • May 2011

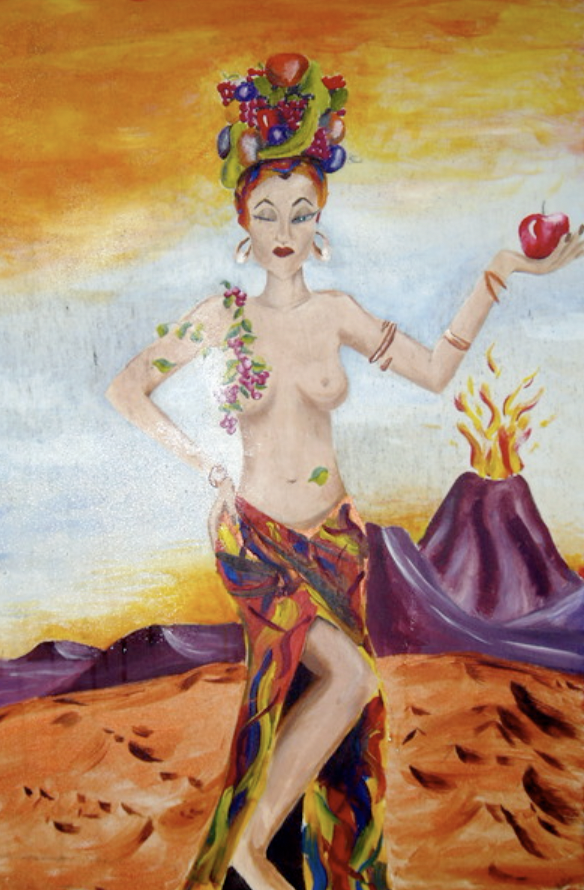

Chiquita

Anonymous • December 2006

Jazz Hands

Linda James • March 2014

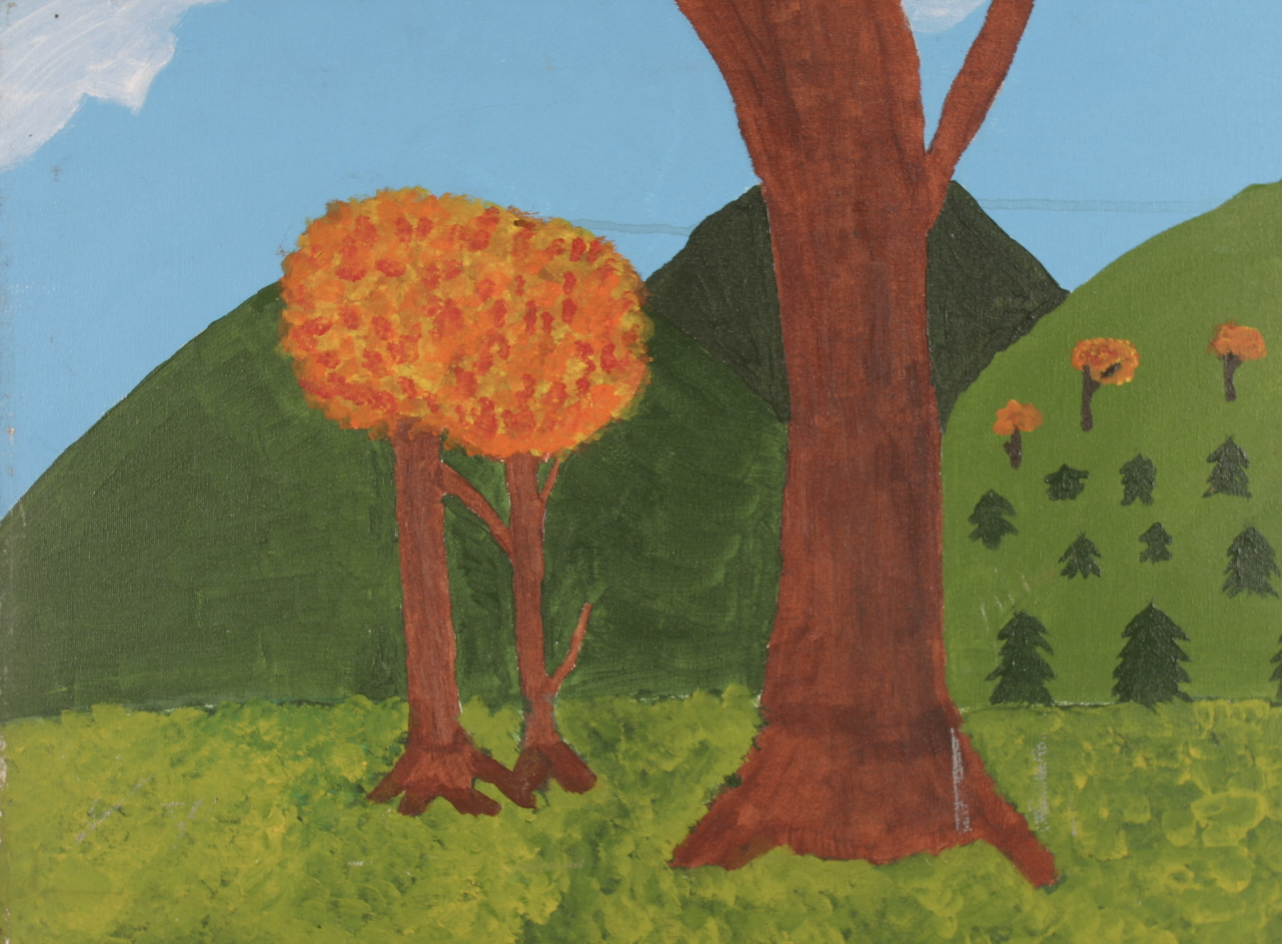

Two Trees in Love

Julie Seelig • May 2006

Baby Atlas

Anonymous • September 2009

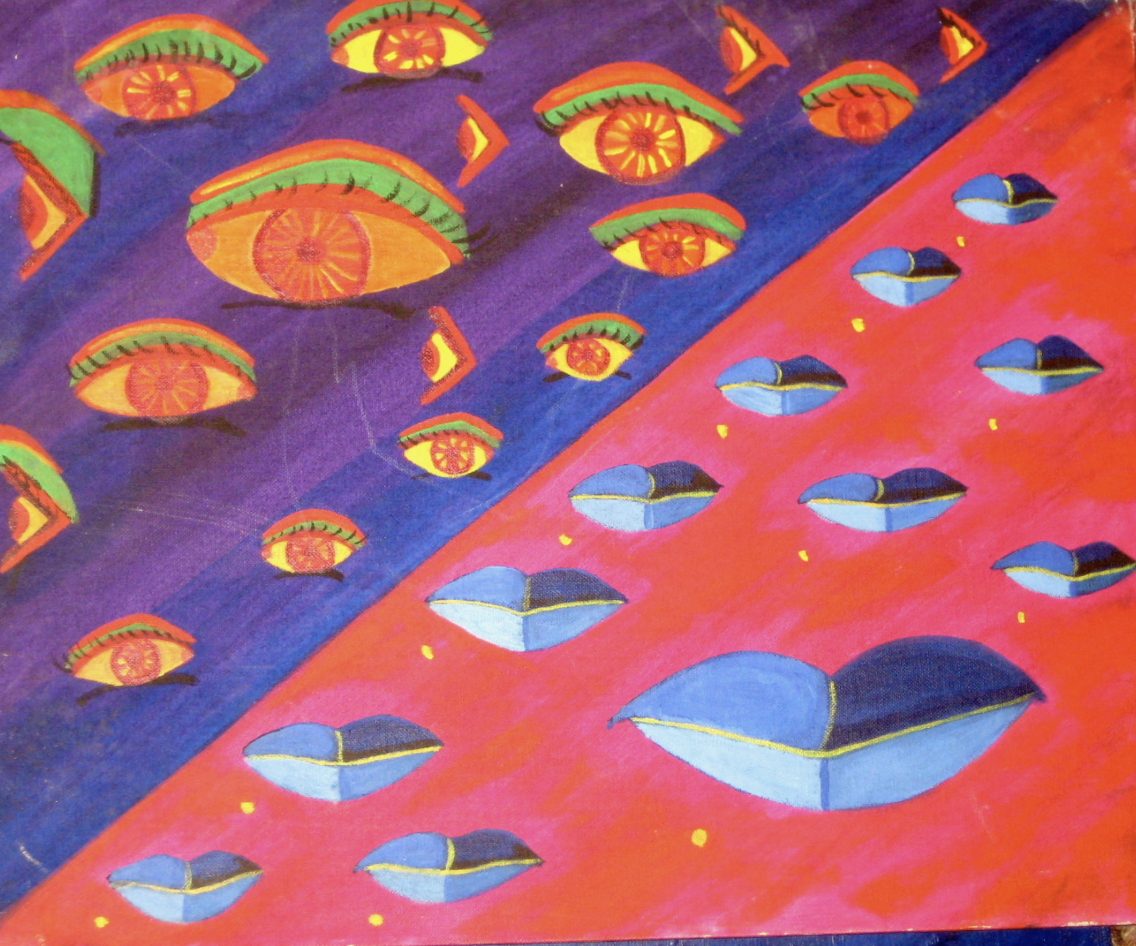

Eyes and Lips

Jeanne Galarneau Kent • December 2008

Madonna and Baby

Anonymous • May 2017

Life on a Barstool

Anonymous • July 1998

The Museum of Bad Art has been mentioned in hundreds of international publications, as well as in Boston-area travel guides highlighting offbeat attractions. It has inspired similar collections or events in Australia, Ohio, and Seattle.

Commedia Beauregard, a theatre company whose mission focuses on translation, was inspired by MOBA's mission to create their Master Works series of short play festivals. The company commissioned six playwrights to write short plays based on MOBA artworks. Master Works: The MOBA Plays was originally performed in January and February 2009 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The plays were based on the MOBA pieces Mana Lisa, Invasion of the Office Zombies, My Left Foot, Bone-Juggling Dog in Hula Skirt, Gina's Demons, and Lulli, Fowl and Gravestone. After moving to Chicago, the company again produced The MOBA Plays in March and April 2011, using three of the original plays and translating three new paintings.

The Dedham Community Theater housed the first MOBA gallery in its basement. Museum visitors can sign a guest book, and leave comments. One Canadian visitor wrote: "This collection is disturbing, yet I can't seem to look away...Just like a hideous car accident." Another visitor observes: "Her nipples follow you around the room. Creepy!"

Response to MOBA's opening and continued success is, for some, evocative of the way art is treated in society. MOBA works have been described as "unintentionally hilarious", similar to the films of Ed Wood. Visitors—and even MOBA staff—often laugh out loud at displays. In Gullible's Travels, Cash Peters contrasted this behavior with what is expected of patrons at galleries such as Southern California's Getty Museum; though viewers might find the art at the Getty equally hilarious, were they to show it they would almost certainly be thrown out.

In 2006, Louise Reilly Sacco participated in a panel discussion with authorities on art and architecture about standards of beauty and ugliness in art, published in Architecture Boston. She remarked that teachers bring high school art students to MOBA, then to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA). Sacco observes, "Somehow MOBA frees kids to laugh and point, to have their own opinions and argue about things. Then they take the experience to the MFA, where they might otherwise feel intimidated... Maybe the ugly ... frees us." Sacco believes that extreme ugliness is more striking than extreme beauty, and it forces people to think more deeply about what is wrong or misplaced. She connects this rigid judgment of what does not conform to beauty with intolerance for physical imperfections in people, noting that such rigidity sometimes causes parents to "fix" the perceived flaws in their children's faces to keep them from suffering later.

The Somerville Theatre once housed a MOBA gallery in its basement. Jason Kaufman, a Harvard professor who teaches the sociology of culture, wrote that MOBA is part of a social trend he calls "annoyism", where mass media venues promote performances and artists who mix the deliberately bad with the clever. The Museum of Bad Art happens to embody this trend, and further illustrates its central aim to mock the judgment system by which people identify what is bad from what is not. For Kaufman, "The beauty of MOBA—though beauty is surely the wrong word—is the way it undermines aesthetic criteria from numerous angles." Amy Levin, describing how American history and culture have been shaped by small local museums, suggests that MOBA is a parody of art itself, and that MOBA's commentary, newsletter, website, and publications mock museums as authorities on what is good art. The director of the Ellipse Arts Center, a gallery in Arlington, Virginia, that hosted a traveling exhibition of MOBA works, was astonished to see people's exuberant laughter because no one visiting the Ellipse had ever responded to art this way. She observed, "If I didn't have a sign on the door, people might not think it's so bad. Who's to say what's bad and what's good?"

Deborah Solomon, in The New York Times Magazine, asserted that MOBA's success reflects a trend in modern art among artists and audiences. The arrival of abstraction and modern art in the early 20th century made art appreciation more esoteric and less accessible for the general community, showing that "the American public ... think[s] of museums as intimidating places ruled by a cadre of experts whose taste and rituals [seem] as mysterious as those of Byzantine priests." Bad art is in vogue, as a movement that rejects the anti-sentimentalism that marked earlier disdain for artists such as Norman Rockwell or Gustave Moreau, according to Solomon. Garen Daly, a MOBA fan on several Boston-area art councils, stated in 1995, "I go to a lot of openings, and sometimes they're pretty damn stuffy." Not only does the Museum of Bad Art offer different fare for the eyes, but instead of the wine and cheese that is provided for most museum and art gallery visitors, a MOBA show provides its patrons with Kool-Aid, Fluffernutters and cheese puffs.

The works in the Museum of Bad Art have been used in academic studies as a standard of reference for low quality art. In one such study, published in Perspectives on Psychological Science, researchers tested the consistency of responses between people asked to make "gut" judgments versus those who gave conscious well-reasoned responses regarding the quality of various pieces of art. The researchers showed respondents images from MOBA and New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and asked them to rate each painting on a scale with two ends representing "Very Attractive" and "Very Unattractive". The study found that those who reasoned in conscious thought were neither more accurate nor as consistent in their ratings. Study participants identified and rated MoMA art higher quality, but those who used conscious reasoning did not find MoMA art more attractive than those who rated with "gut" judgments. Furthermore, the deliberators did not find MOBA art as unattractive as those with quicker response times. The study concluded that people who make quick judgments do so more consistently, with no significant change to accuracy.

In another study that appeared in the British Journal of Psychology, researchers tested how respondents considered balance in artwork composition of differing qualities. Fifteen pairs of works from ArtCyclopedia by artists such as Paul Gauguin, Georgia O'Keeffe, and Georges-Pierre Seurat, and fifteen from MOBA by artists including Doug Caderette, Unknown, and D. Alix were shown to participants. In each, an item in the painting was shifted vertically or horizontally, and respondents were asked to identify the original. The researchers hypothesized that respondents would identify balance and composition more easily in the traditional masterworks, and that study participants would find a greater change of quality when items were shifted in traditional masterworks than they would in MOBA pieces. However, the study concluded that balance alone did not define art of higher quality for the participants, and that respondents were more likely to see that original art was more balanced than the altered version, not necessarily that the traditional art was significantly better composed and balanced than MOBA works.